Load

Training Impulse(TRIMP)

TRIMP measure the impact of exercise.

Given the complexity of exercise (e.g., duration, speed, terrain, weather, and etc.), it is hard to have a standardized measurement for the impact on body.

There are many ways to define TRIMP:

- Training volume - in terms of distances. It is a very simplified approach.

- Effort - e.g., using rating perceived exertion such as Borg RPE scale, which is subjective.

- Average heart rate - it is more objective. However, average may underestimate a mixed speed session when compared with a steady low speed session.

- Exponential heart rate - calculate the weighted average of heart rate reserve, while the weight is exponential in terms of the HR reserve.

Banister first summarized the formula as

where y is a gender scalar (1.92 for men and 1.67 for women).

Note, the TRIMP_{exp} is not normalized for genders.

Impacts

TSB model

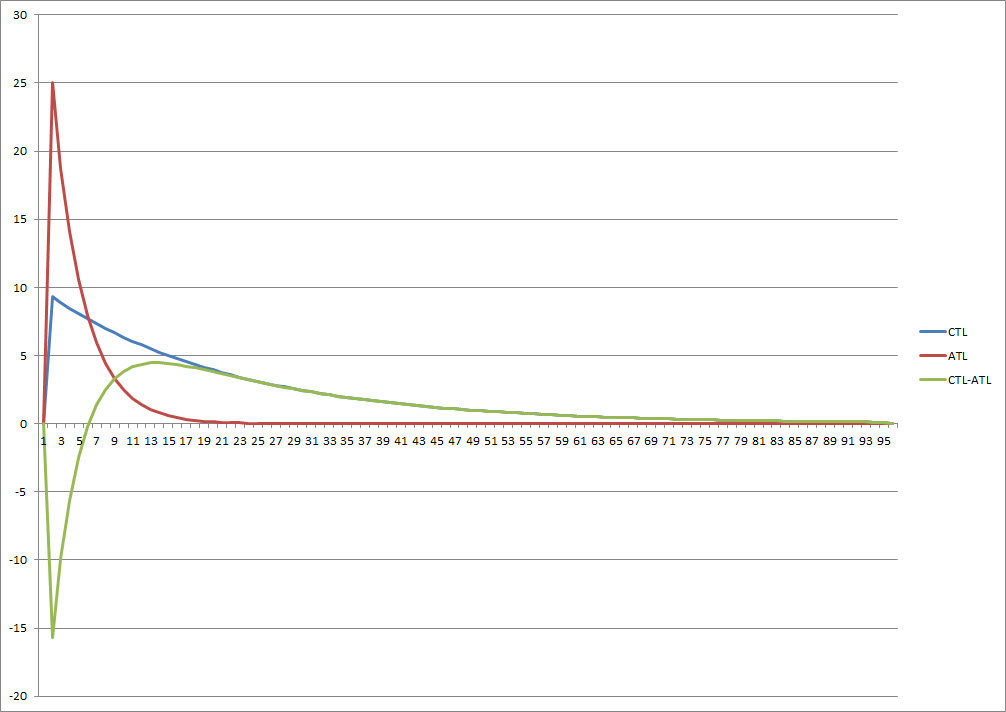

Impact of training can be split into two - Chronic Training Load (CTL) for "fitness", Acute Training Load (ATL) for "fatigue" , which are combined into raining Stress Balance (TSB) for "performance".

Right after a workout, both CTL and ATL have sharp increases, leading to a net drop in TSB (=CTL-ATL). This is expected that you typically feel tired after workout.

Then, both CTL and ATL revert back to the long-term average (0), while the CTL moves more slowly. That means the gained fitness will decay slowly, while the recovery from fatigue is often faster. The net gain is obtained and will last for some time.

Borrowing the plot from fellrnr:

Now, consider there are multiple workouts. If we allow sufficient recovery between workouts (wait until the green curve to reach positive, or ideally its peak), then we can harvest the net gain from that workout.

However, if we rush to the next workout before recovery (while the green curve is still negative), then the body is still in a weak status, meaning it is cumulating net "fatigue", which is likely to lead to over training.

In TrainingPeaks, ATL and CTL are considered to decay exponentially with half life (2.4 and 14.5 days, respectively).

This is a simplified model. If following the discussion above, one will need to wait for more than 1 week to harvest the net performance gain, which is impractical. In practice, atheletes typically train multiple times in a week, accumulating "fatigue".

While in the accumulation phase of the macro training cycle, we do not want the fatigue to be overwhelm leading to overtraining, which leaves the athelete in a risky position for injury, or impacts the atheletes ability to complete quality training.

The TSB model does explain the need of tapering though. To allow the max "performance", about 2 weeks time is needed to reach the highest level.

Limitations

- The model aggregate previous exercises with exponential weights, so it is only meainingful for a relatively narrow window.

- There is no limits on the terms. In particular, extreme training intensity can introduce higher risk of injury, over training, and mental burnout.

- Overtraining may lead to slower recovery (longer half life for ATL), which is not modeled.

- The initial states are hard to get. May need significantly long period to "warm-up".